Build the Flywheel. Not the Funnel.

How category design helps you pull demand instead of chasing it.

There’s a dangerous messaging myth in agtech.

It’s quietly costing companies millions—and no one’s talking about it.

The myth goes like this:

“We just need to get the word out.”

It sounds harmless. Ambitious, even. But underneath it lies a deadly assumption:

That the message already matters.

That people are already listening.

That the problem you solve is already understood.

In agtech, none of these things are true.

The result? Teams scramble. They hire agencies. They chase clicks, impressions, and followers. They tweak taglines. They spend tens of thousands on brand guides and creative briefs. They run Lightning Strikes that light up nobody’s radar. They sponsor trade show booths that get compliments—but not conversions.

And they wonder why nothing sticks.

The hard truth is that the market doesn’t get what you’re doing because you haven’t made it matter.

Until you do, every dollar spent on messaging is just noise—polished, pretty noise.

This isn’t just a marketing failure. It’s a category failure.

And you can’t solve a category failure with copywriting tricks. You need to change the narrative.

A Tale of Two Cities: Better-town vs. Different-ville

Let’s explore this idea with a story.

It’s a story of two towns. Facing the same crisis. With very different outcomes.

Bettertown was proud, proper, and disciplined. When a recession hit, and unemployment soared, the town council felt trapped between two bad options: do nothing or give handouts. Neither felt right, so they invented something they thought was “better.”

They created a relief program—but not just any relief program.

This one was designed to discourage dependence. If you wanted help, you had to prove your desperation. Applications were long. Interviews invasive. Relief officers could show up unannounced to inspect your fridge, budget, and home. The message was clear: help comes with shame.

They thought this would preserve character. Instead, it created resentment.

The unemployed were humiliated, and the employed were smug. Tensions rose, and trust fell. While the worst was narrowly avoided, the town lost something deeper—its sense of unity.

Different-ville took another approach.

They didn’t start with the problem. They started with a principle:

“Unemployment is like a house fire—an unpredictable disaster no one asks for.”

They reframed the situation entirely.

They called it insurance, not welfare. Every resident who’d contributed to the community—by working, paying taxes, or building—had earned the right to claim a payout during hardship. These weren’t handouts. They were claims on value already created.

And they celebrated it.

The first checks were handed out at a town-wide event. Flags. Speeches. Photos with the mayor. It was civic pride, not pity.

When a skeptical reporter asked the mayor, “Isn’t this just clever PR? Haven’t you just renamed welfare by calling it insurance”

The mayor replied:

“What do you mean, calling it insurance? It is insurance.”

Most of our companies are stuck in Better-town.

We build something useful, maybe even powerful. But instead of framing a new future, they describe features, specs, outputs, and capabilities. They assume people will connect the dots.

They don’t.

Because the industry is saturated with noise. And when your messaging echoes the status quo—even unintentionally—you reinforce the very mindset you're trying to change.

If Better-town teaches us anything, it’s this:

Your narrative doesn’t just influence perception. It defines reality.

You’re not selling “better.”

You’re not selling “innovation.”

You’re selling a new mental model—a new way to see what matters.

And that starts with language.

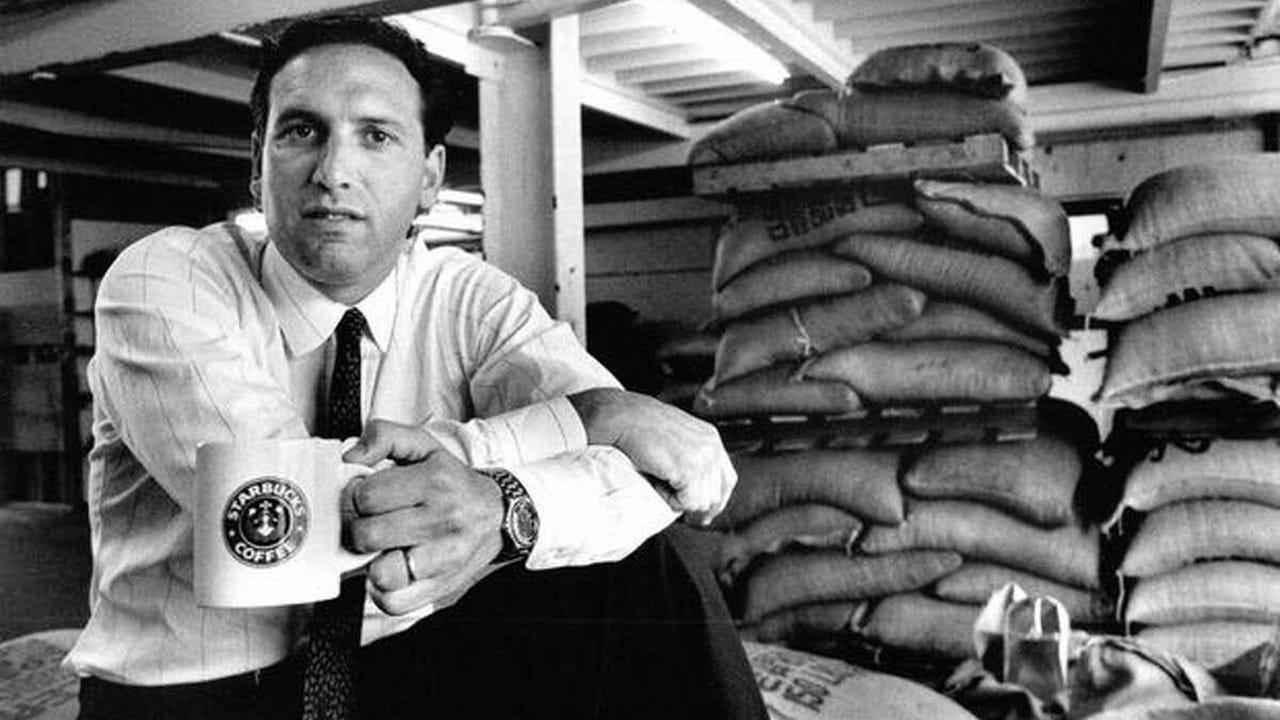

No one understood this better than Howard Schultz.

Schultz wasn’t always a billionaire coffee mogul. He was a kid from the Brooklyn projects.

When he was seven, he watched his father—an unskilled laborer—get injured and immediately fired without benefits or support. His dad collapsed on the couch, broken and bitter, unable to find work that gave him meaning.

That image haunted Schultz.

He didn’t just want a job. He wanted to do work that meant something.

Years later, as marketing director for a tiny coffee and tea company called Starbucks, Schultz visited Italy. What he found wasn’t just espresso—it was experience.

“The energy pulses all around you,” he said. “These places offered comfort, community, a sense of extended family.”

He watched baristas dance behind the counter, pressing espresso, steaming milk, and laughing with customers. It wasn’t a transaction. It was theater. It was ritual. It was human.

He didn’t come home wanting to import better beans. He came home determined to import a story.

At the time, Starbucks sold great coffee beans—but only to a niche elite. Schultz realized they weren’t scaling because they were trying to market a premium product without a premium story.

So he gave Starbucks one. He developed unique language around the brand.

They began to serve coffee by the cup.

They created an inviting, sensory-rich “Third Place.”

They renamed the roles: servers became baristas; they were partners in the business.

Drink sizes weren’t small/medium/large—they were Tall, Grande, Venti.

They didn’t sell coffee with milk. They sold Caffè Lattes.

And just like that, the product stopped being a commodity. It became an experience.

A shift in language creates a change in thinking, which creates an adjustment in action, and leads to a transformation in outcome.

Starbucks didn’t win just because people thought the coffee was better.

They won because people thought they were better when holding a Starbucks cup.

Dunkin’ didn’t get that. In 2008, they ran a double-blind taste test and proudly announced that people preferred Dunkin’ coffee to Starbucks. They launched DunkinBeatsStarbucks.com and bragged about their win.

And yet, Starbucks today dwarfs Dunkin’.

Because coffee wasn’t the point.

The rise of Starbucks wasn't built on the whims of people tasting two unnamed coffees side by side and picking a winner. It was built on the context within which that coffee was enjoyed.

The same insight showed up at a university hospital in Michigan.

A team of researchers interviewed the cleaning staff.

Same job. Same pay. But half said their work was low-skilled and boring. The other half said it was deeply skilled and meaningful.

What was the difference between the two groups?

The language they used to describe their role.

One group said, “It’s just cleaning. Like what you do at home.”

The other referred to themselves as ambassadors—people who formed relationships with nurses, patients, and visitors to create an environment for healing.

Their job hadn’t changed. Their words had.

And because their words changed, their behavior toward their job did, too.

AgTech is full of legendary innovators.

Engineers who’ve built machines that aim, adapt, and learn.

Platforms and sensors that visualize every inch of every acre in real time.

Tools that could fundamentally transform the economics of growing food, fuel, and fiber.

But what happens next?

They take this game-changing technology—and describe it as “a complete agronomy platform.”

They build systems that could redefine decision-making—and call it “next-gen precision.”

They release tools that remove friction, add intelligence, and give growers control, but they market them using the same bloated language as everyone else.

They look at incumbent solutions and the way customers talk about things today and assume they’re permanent. They assume they’re neutral. But they’re not.

It’s designed.

The language customers use was built by your competition.

And the minute you adopt it, you’re reinforcing their worldview. You’re anchoring your new story to someone else’s legacy. And you’re inviting customers to make side-by-side comparisons on their terms, not yours.

This is the subtle failure behind most agtech messaging:

You build something new.

You describe it like something old.

And then you wonder why it feels like no one “gets it.”

The language doesn’t match the leap.

And because the language doesn’t match the leap, the market can’t feel the difference.

When that happens, all your innovation gets flattened. You become Better-town.

You end up reinforcing the category king instead of dethroning them.

Here are two real-time examples:

Verdant Robotics

Their current messaging?

“Precision you can see. Results you can trust.”

“The future isn’t spraying. It’s aiming.”

Now let’s translate that for a skeptical grower:

“You do spraying? So does Deere.”

“You aim? So does See & Spray.”

To be clear—Verdant’s tech might be extraordinary. It’s not just spraying. Their machine is tractor-mounted, plant-level, multi-tasking, and well-suited for specialty crops. But none of that matters if the message sounds like an echo.

Verdant is using language Deere already owns.

And in the mind of the customer, that means Verdant is the imitation. Not the originator.

A Mental Rule of Thumb: When a challenger borrows the king’s language, the king always wins.

CropX

They say:

“Sustainable and successful farming.”

“The Complete Digital Agronomy Platform.”

Try saying that out loud to a retailer or grower and watch their eyes glaze over.

Why?

Because “sustainable” and “successful” have become white noise. Everyone from Bayer to the USDA has flooded the zone with those terms.

“Complete platform” is so common it means nothing. Worse, it raises questions: What does “complete” mean? Is it modular? Do I lose control?

These aren’t answers. They’re sophisticated word salads of ambiguity.

And when your message is vague, your product gets lumped into the “maybe” pile.

This all comes back to one of the core laws from Ries & Trout:

Marketing is not a battle of products. It’s a battle of perceptions.

And the most powerful perception in any market is a single word or phrase.

Volvo owns “safety.”

Climate FieldView owns “field visibility.”

BMW owns “performance.”

SwarmFarm Robotics owns “integrated autonomy.”

FedEx owns “overnight.”

Google owns “search.”

Zoom owns “video calls.”

John Deere owns “precision.”

When you hear the word or phrase, you think of the brand.

When you hear the brand, you think of the word or phrase.

What does Verdant own?

What word belongs to CropX?

If you can’t answer that instantly, neither can your customers.

That’s a messaging problem. But more importantly—it’s a category problem.

You don’t need a campaign. You need a category.

This is the part where most teams panic.

They realize their message isn’t working. So they double down on tactics. They spend more money, try new channels, refresh the website, swap one generic phrase for another. They chase clicks. They A/B test headlines. They hand it all off to a creative agency and hope for the best.

But what they’re facing isn’t a creative problem. It’s a category problem.

Most agtech messaging fails not because the product is weak, but because the frame is wrong.

You’re playing someone else’s game.

The language you're using? Inherited.

The positioning you're reinforcing? Already claimed.

The problem you're solving? Never clearly defined.

You’re polishing a story that isn’t yours.

And here’s the hard truth: You can’t out-message a broken frame. You have to build a new one.

Which is why companies that win don’t just compete.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ag Done Different to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.