“Some men see things as they are and say 'Why?'

But I dream things that never were, and say 'Why not?”

- George Bernard Shaw

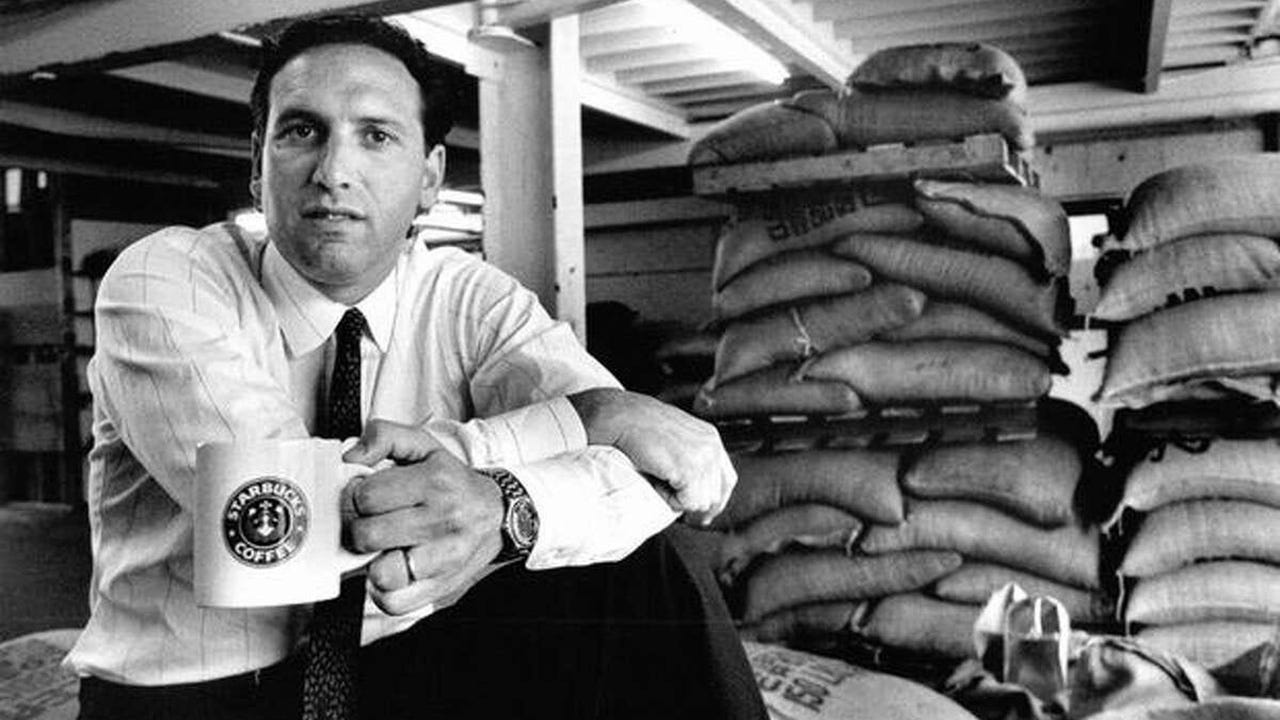

Howard Schultz thinks a great deal about the language he uses. Even today, he carries himself with the calm intensity of a leader on a mission. He is not the type of person who wings a speech or flippantly addresses a crowd. He weighs his words with care and speaks not just to be heard but to be understood. This has been an incredible asset to him throughout his career, and it is a skill he owes, at least in part, to the obvious role language has played in shaping his life.

Once, when he was seven, Schultz walked into his family’s two-bedroom apartment just as his mother hurriedly threw on her coat and headed out the door. “Dad had an accident,” she said. “I have to go to the hospital.”

Howard’s father never graduated high school. Like so many others of his station in life in the 1960s, when he couldn't work, he was dismissed from his job without health insurance, worker’s compensation, or anything else to fall back on. The family was without income and stressed financially, but even more importantly, Howard saw what he would later call “the fracturing of the American dream.” He watched his father lay slumped on the family couch with no hope of doing work he found meaningful.

That's when Schultz decided that when he grew up, his work would not only pay the bills, it would mean something.

He discovered that meaning in the spring of 1983 on a trip to Italy as the new marketing director for a small coffee and tea retailer called Starbucks.

His boss sent him to Italy to represent Starbucks at a tradeshow, but it was the Italian espresso bars that captivated him.

“I was fascinated,” Schultz still remembers the first coffee bar he ever visited. “Behind the counter, a tall, thin man greeted me cheerfully, “Buon giorno!” as he pressed down on a metal bar, and a huge hiss of steam escaped. He handed a tiny porcelain demitasse of espresso to one of the three people who were standing elbow-to-elbow at the counter. Next came a handcrafted cappuccino, topped with a head of perfect white foam. The barista moved so gracefully that it looked as though he were grinding coffee beans, pulling shots of espresso, and steaming milk at the same time, all the while conversing merrily with his customers. It was great theater.”

For the next week, Schultz basked in that theater, walking the streets of Milan from coffee bar to coffee bar. At the time, there were 200,000 coffee bars in Italy - 1,500 in Milan alone. It was obvious to see why.

“The energy pulses all around you,” he recounted. “Italian opera is playing. You can hear the interplay of people meeting for the first time, as well as people greeting friends they see every day at the bar. These places offered comfort, community, and a sense of extended family.”

In one coffee bar, Schultz mimicked a local and ordered something called a “caffè latte.”

He expected the drink to be just coffee with milk but watched in amazement as the barista made a shot of espresso, steamed a frothy pitcher of milk, and poured the two into a cup with a dollop of foam on the top. After taking the first sip, he knew that this drink could help him sell the experience of Italian coffee to Americans.

Schultz realized that while Starbucks sold great coffee beans, they were failing to make the product accessible to anyone other than a small elite of gourmet coffee drinkers. It was like their product was a secret hiding in plain sight, just waiting to be discovered. Howard Schultz decided that, someday, Starbucks would find a way to translate its high-end retail concept into a customer experience that could spread to the broader population.

They would bring the ritual and romance of coffee bars in Italy to America. They would serve coffee by the cup. They would cultivate an atmosphere of belonging and community. And they would use language to bring it all to life.

Starbucks ended up becoming the most valuable coffee company in the world.

How Language Shapes Thinking

Imagine you work on staff at a university hospital. Your job is to clean patients’ rooms, hallways, and common areas. You have a clear description of your job, but how do you perceive the meaning of the work you do? In 2001, researchers at the University of Michigan set out to answer this question.

The team randomly selected a number of cleaning staff members at the local university hospital and interviewed them. They shadowed them on the job and surveyed them about their work. How long had they worked at the hospital? What units and floors did they work on? What shifts were they generally working? How well were they compensated for the work they did?

But when they got to the question, “How much skill does your job require?” the cleaners were split. About half of them answered that the job was quite low in skill, while the other half described the job as being very high in skill and requiring years to master.

The researchers were perplexed. Here, you had similar people doing the same job for the same pay, and they saw the job in a completely different way. What, they wondered, could account for such a split?

When they dug further into the data, they discovered a clear point of differentiation. On the questions about the kinds of things that went into the tasks, the relationships, the interactions, and the way they thought about their work, the individuals who viewed their job as requiring very little skill talked almost exclusively about their role as it was written in the official job description. When asked outright how they identified their role in the organization, they gave the researchers their official title. "It's just cleaning,” they would say. “It's like what you do at home.”

On the other hand, the group who viewed their work as being very highly skilled talked about doing things like forming relationships with the nurses and the clerks on their units so that they could adapt the timing, the chemicals, and the materials they were using in their cleaning so that it would better facilitate the healing or the comfort of the patients in those rooms. They mentioned forming relationships with patients and with patients' visitors that sometimes went on for years after a patient was discharged. They talked about doing things like taking patients from point A to point B. They helped elderly visitors navigate the Byzantine layout of the hospital so the patients wouldn't be worried about their visitors finding their way out. They made note of patients who hadn't had visitors in a couple of days so they could double back and spend some time speaking with them. When the highly skilled cleaners were asked to define their role at the hospital, they called themselves “ambassadors” and talked about playing their part in creating an environment for healing.

“This is not just a trick of the mind,” says Amy Wrzesniewski, one of the lead researchers on the project. “This is not just doing the same kind of work but thinking about it differently. [The way people describe their work] actually actively influences what it is people are doing on the job, how it is they're doing it, when they're doing it, and with whom the work is done. It changes the job description in ways that are pretty serious. If we had done this project through reverse induction, we would have made the assumption that these two different groups of cleaners were in two completely different jobs.”

The language the cleaners used to describe their work changed the way they thought about that work, and thinking about their work in this way caused them to take corresponding action, leaving them working in one of two distinctly different jobs. They were either a “custodian” or an “ambassador.” They either worked the job as it was described for them or went above and beyond. They either found the work to be highly skilled and meaningful or low-skilled and monotonous.

A shift in language creates a change in thinking, which creates an adjustment in action and leads to a transformation in outcome.

For some reason, this is a very difficult lesson for us to learn. We have, I think, developed a singular understanding of what it takes to build a breakthrough and change buyer behavior. We look at the incumbent solutions and the way customers talk about things today, and we assume that is static, that they have always talked this way. We miss the fact that the language our customers use was designed by our competition, and the minute we mindlessly adopt it, we further establish the conventional way of doing things in the customer’s mind.

This edition of AgTech Marketing Insights is an attempt to explore the ramifications of that error. When we see our competition and customers using a particular term or phrase, why is it that we assume we must do the same? And what does it take to be a person or company who refuses to accept the conventional premise - like the University of Michigan hospital cleaners or Howard Schultz and the Starbucks Corporation?

From Commodity to Experience

The Starbucks we all know today was born on August 18, 1987. That’s when Howard Schultz took over as CEO and owner. At the time, the company’s roasting plant and headquarters were located in a narrow, old industrial building on Airport Way in Seattle's Georgetown district.

Because Schultz had very little executive management experience, he recruited a couple of experts to help. The first was Dave Olsen, a passionate coffee aficionado who had run a small, successful cafe in Seattle’s University District for years. After Olsen signed on, they recruited Lawrence Maltz, a seasoned executive who had previously managed a public beverage company. Lawrence became an early investor in Starbucks and joined the company as executive vice president.

“Our little management team didn’t examine our motives for wanting to grow fast. We set out to be champions, and speed was part of the equation,” said Howard Schultz. “Perhaps we could change the way Americans drank coffee.”

Starbucks’s strategy was built around the two things that stuck out to Howard when he visited Italy years before. The first was the quality of the coffee. Most of the coffee served by the cup in the U.S. at the time was what Schultz pejoratively referred to as “swill.” Priced around $0.50 per cup, it was an inexpensive way to get the caffeine fix you needed to get through the day. The only real question was if you wanted a small, a medium, or a large. Schultz and Starbucks changed that. They priced their coffee at the seemingly outrageous price of nearly $2. They brewed full flavor, dark arabica coffee beans, and infused the drink with the Italian inspiration for their store concept by naming their size options tall, grande, and venti. Starbucks didn’t serve espresso with milk; they introduced Americans to the caffè latte. They put drink names on their menu that many had ever heard of, like the Macchiato, the Cappuccino, and the Frappuccino.

The second element of their strategy was the inviting atmosphere of their locations. Most American coffeehouses in the late 1980s were optimized to get customers in, out, and on their way. Starbucks borrowed from Italian espresso bars by cultivating a sense of community, warmth, and what Howard Schultz called “the romance of coffee” in their stores.

“More and more, I realize, customers are looking for a Third Place, an inviting, stimulating, sometimes even soulful respite from the pressures of work and home,” said Schultz.

The team understood that their product was more than coffee. It was the “Starbucks experience.”

The company didn't call their employees staff. They referred to them as partners and gave them benefits and stock in the company. The airline executive, Herb Kelleher, who founded Southwest Airlines in the late 1960s, famously said, “You have to treat your employees like customers.” Kelleher and Schultz shared the belief that when employees feel valued and respected, they are much more likely to provide exceptional service to customers.

And just like the Michigan University Hospital study would show years later, a critical element of making employees feel valued and respected revolved around the language you used to describe them and their roles within the organization.

“Starbucks didn't just redefine coffee; they redefined coffee as an experience, so they needed their own language,” says language strategist Lee Hartley Carter. “Going to get a Starbucks coffee in the middle of the day is no longer about getting a cup of coffee. It's the modern-day smoke break. It's an experience, it's a release. You feel differently about yourself when you come out of it. Of course you need different language to describe that.”

That strategic shift in language didn't just change the way employees and customers thought about Starbucks coffee, it created an altogether different environment or context for coffee to be consumed.

In 1987, Howard Schultz had promised investors that Starbucks would open 125 stores over the next 5 years. He later increased that number to 150. By 1992 when the company went public, they had 165 stores. By 2000, the “Starbucks experience” had spread to 5,000 locations worldwide and made another leap to 28,000 stores in the 2010s. Today, the company has 35,711 stores in 80 countries and is worth $105 billion. And it all started with the strategic use of language which changed thinking and altered the way a broad portion of the world has come to experience coffee on a daily basis.

Starbucks is proof that you can, in fact, reinvent a commodity. Even when it is (at the time) the second-highest-traded commodity in the world. The key is understanding precisely what business you’re in and acting accordingly.

“We aren’t in the coffee business, serving people,” says Schultz. “We are in the people business, serving coffee.”

The Hedge of Intentional Language

One of the things that happened to Starbucks as the company began to succeed on the global stage was that they became a target for incumbent competitors in the space. In 2008, for example, Dunkin’ Donuts partnered with A&G Research to run a double-blind taste test comparing Dunkin’ Donuts coffee to Starbucks in 10 major cities across the United States. They found that 54.2% of people favored Dunkin’ Donuts Original Blend, while only 39.3% chose Starbucks, and 6.3% had no preference.

Dunkin’ Donuts executives were thrilled. Here was an opportunity to knock Starbucks down and peg. Dunkin’ opened its doors in the 1950s and had watched Starbucks expand with growing alarm and annoyance. By 2008, Starbucks had more than 16,000 stores worldwide, nearly twice as many as Dunkin’s 8,800 locations. But now everything was different. Dunkin’ had the taste test to prove it.

The company excitedly planned a marketing campaign around the taste test results. They put out a series of press releases and even bought the domain DunkinBeatsStarbucks dot com.

"Try the coffee that won," the Dunkin' advertisement urged. "And see why America really does run on Dunkin'."

But the results never materialized in favor of Dunkin’. In fact, over the next 15 years, Starbucks grew to be more than 3 times larger than Dunkin’ in store size and blew the older chain out of the water in revenue. In 2023, Starbucks posted annual revenues of $35.9 billion compared to Dunkin’s $1.4 billion.

Hopefully by this point, you see the fatal flaw in the attack from Dunkin’. The rise of Starbucks wasn't built on the whims of people tasting two unnamed coffees side by side and picking a winner. It was built on the context within which that coffee was enjoyed.

The cleaners at the University of Michigan Hospital didn't change their views on their job and then use different words to describe what they did. They used different words to describe their role at the hospital, and as a result, they changed their perspective on the job itself and conducted themselves accordingly.

We spend a lot of time talking about disruptive, innovative products that have changed the way we live our lives. We don’t spend enough time discussing the context and conditions under which those products gain adoption, ultimately changing our world. Howard Schultz is worth $3.1 billion today, not because he brewed great coffee, but because he created a great paradigm through which his coffee could be properly valued and shared with new audiences.

The stories of Starbucks, the university hospital cleaners, and Dunkin’s failed campaign, remind us that the goal of our marketing and commercial activities is not to prove to our audiences that we are correct, it's not to hit them with facts and a spreadsheet-derived ROI they simply can’t refuse. The goal of our marketing is to change the story running through our customer's minds. To talk smarter, not louder.

Make something different. Make people care. Make fans, not followers.

Do you want to learn how to create a message that helps you design change, stand out from the crowd, and cut through the noise? Register for our next cohort series today!

The cohort begins on March 5th.