The Cat, the Fox, and the Death of the Conventional Value Proposition

Why Most Value Propositions Fail—and What to Do Instead

"Limitation is vital. The first step toward a well-told story is to create a small, knowable world... The constraint that setting imposes on story design doesn’t inhibit creativity; it inspires it." — Robert McKee

"The formulation of the problem is often more essential than its solution, which may be merely a matter of mathematical or experimental skill." — Albert Einstein

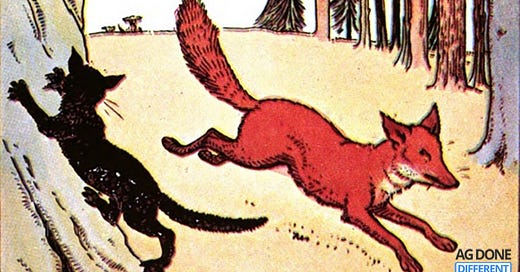

One sunny day, a cat and a fox were making their way through the woods. As they walked, they talked about their shared enemy—the dog—and how they’d escape if he attacked.

"I have countless clever tricks to avoid being caught," the fox bragged.

Just then, they heard barking. Without a second thought, the cat said, "I only know one way," and shot up a tree to safety.

Meanwhile, the fox hesitated, pacing back and forth, paralyzed by his own options. Before he could pick one, the dogs arrived, captured him easily, and dragged him away.

The fox’s mistake? Believing that more options meant more security. In reality, more options led to indecision, confusion, and, ultimately, a brutal ending.

Most companies in agtech today are the fox—obsessed with offering countless options and features in a desperate bid to please everyone.

The result? Confused customers and a message that falls flat.

Here’s the hard truth: the traditional value proposition is dead.

No one wants to read a glorified feature list that makes you sound like everyone else.

The reality is that most “value propositions” are just bland descriptions of what a product does, with no real point of view.

Here’s the brutal truth: customers don’t care about your features.

They care about the problem you solve—and more importantly, about seeing that problem in a way they’ve never seen it before.

When you bury them in a laundry list of features, you don’t multiply value—you dilute it.

This is what psychologists call the dilution effect: when people are overwhelmed by both relevant and irrelevant information, they can’t separate the wheat from the chaff. They end up averaging everything together, which drags down the perceived value of your message.

If your value proposition reads like a buffet menu, you’re not building a category—you’re confusing the heck out of your customers, investors, and partners.

Your customer isn’t sitting around with a checklist of features, hoping you’ll tick all the boxes.

They want to know:

What’s the problem you’re solving?

Why should they care right now?

How will their world change if they buy what you’re selling?

This is where the old-school value proposition fails. It doesn’t challenge how people think—it just gives them a pile of options and hopes they pick one.

And hope is a terrible strategy.

Legendary marketers don’t sell products; they sell the problem.

They don’t just describe a solution—they create a new lens through which customers see the world. This is what the best marketers call a Point of View (POV).

A powerful category POV does three things:

It names a problem your target audience didn’t even know they had.

It reframes that problem in a way that makes your solution the obvious answer.

It makes people say, “How did we live without this?”

If your POV is a laundry list of features, you’re doing it wrong. You’re the fox—paralyzed by your own cleverness—while your customers, overwhelmed by options, choose nothing.

To craft a POV that grabs attention and doesn’t let go, start with these questions:

What’s the painful problem I can solve better than anyone else?

What transformation does my product create for my customers?

What happens if they do nothing?

As Alfred Hitchcock said, "Drama is life with the dull parts cut out of it."

Your POV needs a villain (the problem), a hero’s journey (the transformation), and a clear consequence of inaction.

A bland value proposition is worse than none at all because it creates the illusion of strategy.

It makes you think you’re telling a story when you’re really just reading a spec sheet.

It’s time that we bury the traditional value proposition once and for all.

Instead, we need to build a category POV that teaches our audiences to think about the problem they face differently—so differently that our solution feels like the only answer.

Make something different. Make people care. Make fans, not followers.